Your cart is currently empty!

Category: Car History in London

-

Car History Related to London – How Number Plates Got Here!

London Motoring History Quiz

Think you know London’s rich automotive past? From the first traffic lights to the birth of iconic vehicles, our city has a story to tell. Test your knowledge and see if you can earn a perfect score!

Quiz Complete!

Your final score is:

The Engine of the Metropolis

A Comprehensive History of the Automobile in London

Introduction

This report charts the profound and often contentious 140-year relationship between London and the automobile. From the first sputtering, illegal journeys on cobbled streets to the silent hum of electric vehicles navigating the Ultra Low Emission Zone, the car has been more than a machine; it has been an agent of radical transformation. It has redrawn the map of the capital, fueled its suburban expansion, defined its industrial prowess, and become an indelible part of its cultural identity. This history is a narrative of tension: a constant struggle between the promise of personal liberty and the reality of collective congestion, between technological progress and environmental consequence, and between the desire for speed and the need for safety. We will explore how London, more than perhaps any other global city, has perpetually grappled with this dichotomy, moving from a city that first resisted, then embraced, and now seeks to tame the automobile.

Part I: The Horseless Carriage Arrives (1884 – 1914)

The Age of the Red Flag: London Before the Car

The streetscape of late Victorian London was powered by over 300,000 horses. The first self-propelled vehicles arrived suppressed by the “Red Flag Acts,” which mandated a person walk ahead of any vehicle with a red flag and imposed a 2 mph speed limit in cities. Pioneers like Frederick Simms and The Honourable Evelyn Ellis challenged the law’s absurdity.

Emancipation and the Dawn of a New Era

The Locomotives on Highways Act 1896, the “Magna Carta” for motorists, abolished the red flag and raised the speed limit to 14 mph. It was celebrated with the first “Emancipation Run” from London to Brighton, an event still commemorated today.

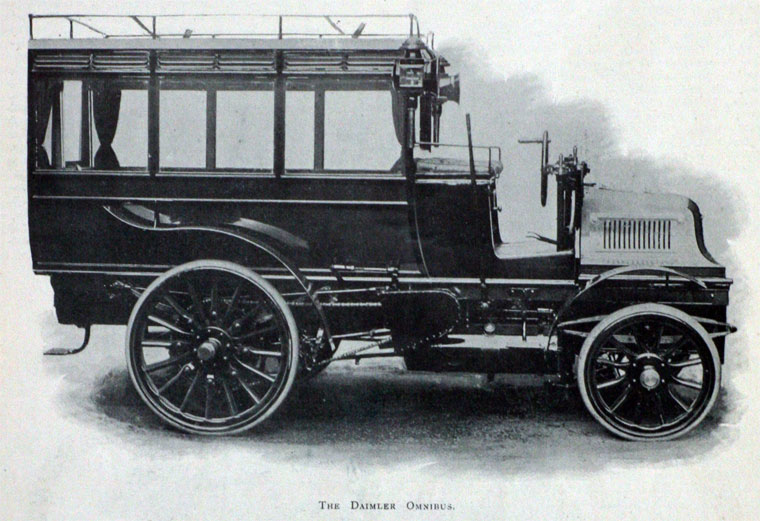

The First London Motors and Their Makers

London became the commercial heart of motoring. The Hon. Charles Rolls founded one of Britain’s first car dealerships here in 1903. High-performance manufacturing thrived with D. Napier & Son in Acton and Bentley Motors in Cricklewood. The Motor Car Act 1903 led to the London County Council issuing the legendary ‘A 1’ number plate.

A City Reacts: Wonder, Resentment, and Regulation

The car’s arrival sparked public hostility over danger and nuisance. The conflict led to the formation of the RAC and AA and forced state intervention, resulting in the first Highway Code (1931) and the Road Traffic Act (1934), which introduced the 30 mph limit and “Belisha beacon” pedestrian crossings.

Part II: The Car Remakes the City (1918 – 1970)

The Suburban Explosion and the Arterial Road

The interwar years saw an explosion in car ownership, fueling the rapid expansion of London’s suburbs. This led to a massive road-building boom, including the Great West Road and the North and South Circulars, creating a new, decentralised model of London built around the private car.

London’s Industrial Heartbeat: From Dagenham to Kew

London was a major centre of vehicle manufacturing. Ford Dagenham, opened in 1931, was one of the largest factories in Europe, producing nearly 11 million vehicles. Other manufacturers included Chrysler in Kew and D. Napier & Son in Acton’s “Motor Town”.

Icons of the Street: The Black Cab and the Routemaster

London produced two iconic vehicle designs. The Black Cab’s unique manoeuvrability was defined by its mandated 25-foot turning circle. The AEC Routemaster bus (1956) was a masterpiece of post-war engineering, perfectly suited to the city’s congested streets.

The Thrill of Speed: London’s Racing Circuits

To bypass restrictive speed limits, dedicated racing circuits were built. Brooklands (1907) was the world’s first purpose-built circuit. Within London, Crystal Palace park hosted races from 1927, attracting legendary drivers.

Part III: Taming the Traffic (1970 – Present)

Encircling the Metropolis: The M25 Orbital

Completed in 1986, the M25 was meant to solve congestion but failed spectacularly, quickly becoming “the world’s biggest car park.” Its failure demonstrated the principle of induced demand and created the political space for demand management.

The Price of Movement: Congestion and Emissions Charging

The London Congestion Charge was introduced in 2003, reducing congestion by 30%. This success paved the way for schemes targeting air pollution: the Low Emission Zone (LEZ) from 2008, and the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) from 2019, which now covers all London boroughs.

London on Screen: The Car as a Cultural Artefact

London’s streets have been the backdrop for iconic movie cars, from the Mini in The Italian Job to James Bond’s Aston Martin DB5. The car has been essential in defining the character of the capital on screen.

The Capital’s Enduring Passion: The Classic Car Scene

Despite difficulties, London maintains a vibrant classic car culture with clubs, major events, and world-class institutions like the Brooklands Museum and the London Transport Museum ensuring its rich heritage is a living part of the city.

Part IV: The Road Ahead

The Electric Revolution

London is at the forefront of the transition to electric vehicles (EVs), driven by a strategy to become a net zero-carbon city by 2030. The major challenge is building charging infrastructure for the 60% of Londoners without off-street parking.

The Autonomous Horizon

London is a key testing ground for autonomous vehicles (AVs). The UK’s Automated Vehicles Act 2024 has created a legal framework for their deployment, potentially as soon as 2026. The future will depend on how the city integrates this technology, likely favouring shared fleets over private ownership.

London’s Automotive Pioneers: A Deep Dive

Families, Legacies, and Modern Connections

The Trevithick Dynasty: Engineering Excellence Across Generations

Richard Trevithick (1771-1833): The Pioneer

Richard Trevithick’s story begins with humble origins in Cornwall’s mining heartland. Despite being described by his schoolmaster as “disobedient, slow and obstinate,” Richard displayed extraordinary engineering intuition. His marriage in 1797 to Jane Harvey connected him to Cornwall’s premier engineering family.

The Next Generation: Francis Trevithick (1812-1877)

Richard’s son, Francis, became prominent in continuing the family engineering legacy. His career achievements included appointments as Locomotive Superintendent for the Grand Junction Railway and later the London & North Western Railway at the new Crewe Works. In 1872, he wrote and published his father’s biography, preserving Richard’s legacy for posterity.

Modern Trevithick Legacy

The Trevithick Society, established in 1935, continues Richard’s legacy today. This registered charity hosts annual Trevithick Day celebrations in Camborne, maintains premises at King Edward Mine, and publishes works on Cornish industrial history. Trevithick Day 2025 continues to draw steam engine enthusiasts from across the UK.

The Simms Automotive Empire: From Patents to Power Systems

Frederick Richard Simms (1863-1944): The Motor Industry Catalyst

Frederick Simms became arguably the “Father of the British Motor Industry”. His pivotal 1889 meeting with Gottlieb Daimler led to him securing British rights to Daimler’s engine patents. His entrepreneurial achievements were extraordinary, including founding the Daimler Motor Syndicate (1893), the RAC (1897), and the SMMT (1902). His company, Simms Motor Units Ltd, became a principal supplier of magnetos to armed forces in WWI. The factory in East Finchley was later acquired by Lucas CAV and is now commemorated by Simms Gardens.

Rolls-Royce: Aristocracy Meets Engineering Genius

Charles Stewart Rolls (1877-1910): The Aristocratic Pioneer

Born in Berkeley Square, London, Charles Rolls died tragically in 1910 at age 32, becoming Britain’s first aviation fatality. With his two brothers also dying without children, the direct male line ended. The family estate, The Hendre, eventually became The Rolls of Monmouth Golf Club.

Sir Henry Royce (1863-1933): Engineering Perfectionist

Henry Royce came from humble origins and was forced into child labor at age nine. He never married and had no children. His legacy continues through the Royce Scholarship for young engineers.

The Bentley Legacy: Racing Heritage Without Descendants

Walter Owen “W.O.” Bentley (1888-1971): The Performance Pioneer

W.O. Bentley founded his company in 1919 in Cricklewood, North London. He married three times but had no children. The original “Bentley Boys” were wealthy amateurs who raced his cars. Today, the Bentley Drivers Club, founded in 1936, continues to preserve his legacy.

Aston Martin: Complex Family Connections and Modern Preservation

Lionel Martin and Robert Bamford founded the company in 1913. The company was saved from bankruptcy by Count Louis Zborowski. Recent research has revealed connections between Aston Martin’s early years and the Bligh family of coachbuilders, who worked on early race cars.

Contemporary Heritage Preservation: Institutional Legacies

The British Motor Industry Heritage Trust (BMIHT), established in 1983, is the primary guardian of Britain’s automotive heritage, operating the British Motor Museum at Gaydon. The London Transport Museum also preserves London’s transport evolution, supported by substantial funding from its Friends organization for restoration projects.

Conclusion

The history of the car in London is a compelling 140-year narrative of co-evolution, conflict, and adaptation. A clear cycle emerges: a disruptive technology arrives, it reshapes the city, its success creates negative consequences, and the city is forced to innovate with policy to manage them. From the Belisha beacon to the ULEZ, London has been in a perpetual state of reaction to the automobile, constantly seeking to balance the individual freedom it offers with the collective costs it imposes.

Today, as London stands on the cusp of the next great automotive transformation—the shift to electric and autonomous mobility—it faces challenges that are echoes of those it confronted in the 1890s. The crucial lesson from London’s long history with the car is that technology alone is never the answer. The city’s future will be defined not by the capabilities of the vehicles on its streets, but by the wisdom of the policies that govern them.